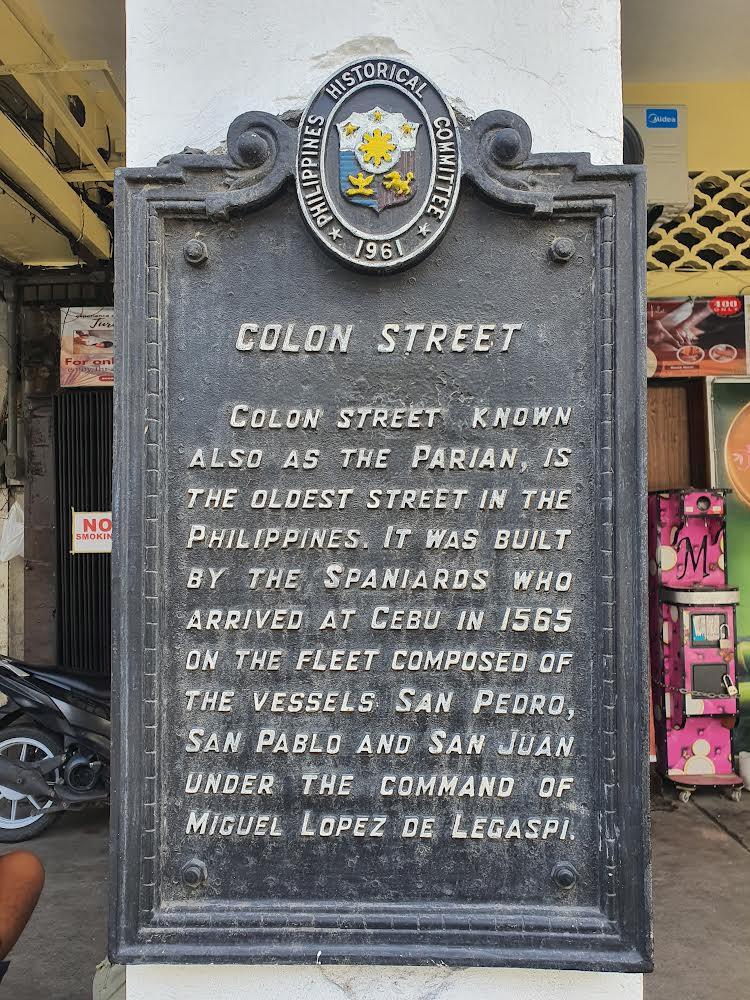

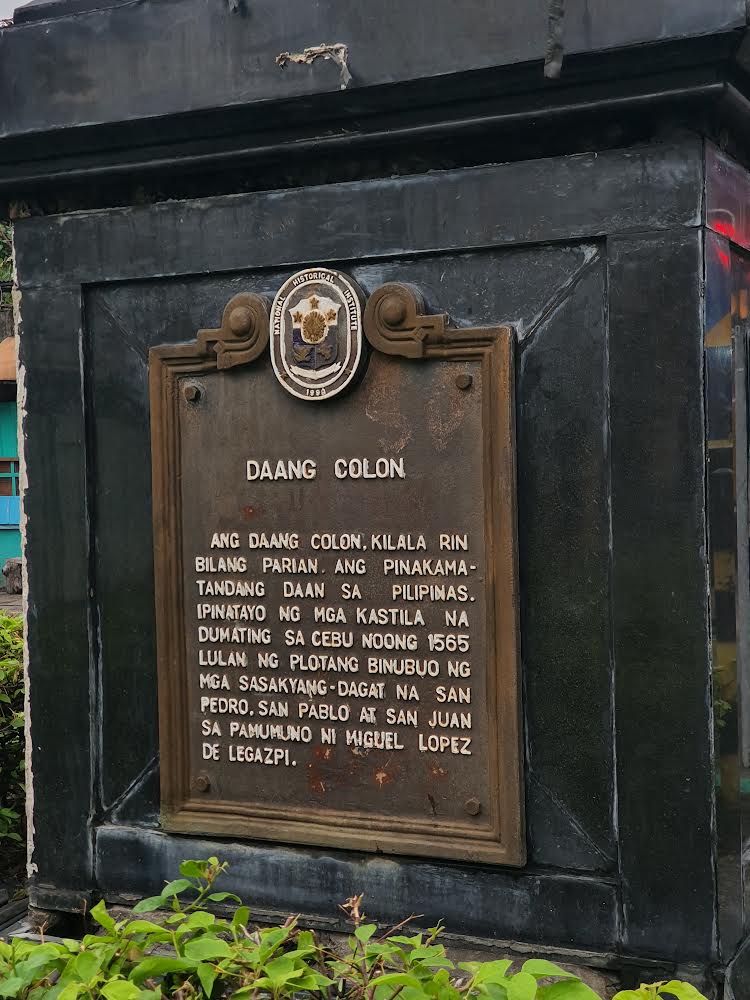

This is probably by far the oldest fake news in the country today. And it has tricked even the nation’s guardian of historical authenticity and accuracy, the National Historical Institute (now the National Historical Commission of the Philippines), which placed not one but two national historical markers on this street, one in 1961, and another 38 years later in 1999.

It is also an object lesson at how unfounded claims can take on a life of their own, made worse in this day where the speed with which fake news gets passed on through social media platforms runs in mere nanoseconds. And sadly, this is not the only false claim to come out of Cebu.

But, like most fake news, this is one that had a very simple but ingenious beginning.

Evolution of a Myth

There is no extant Spanish-era document or map, published or unpublished, that has come to light claiming that Colon Street was the first trail, road, or street that the Spanish built, contrary to the claim made in the 1961 NHI marker.

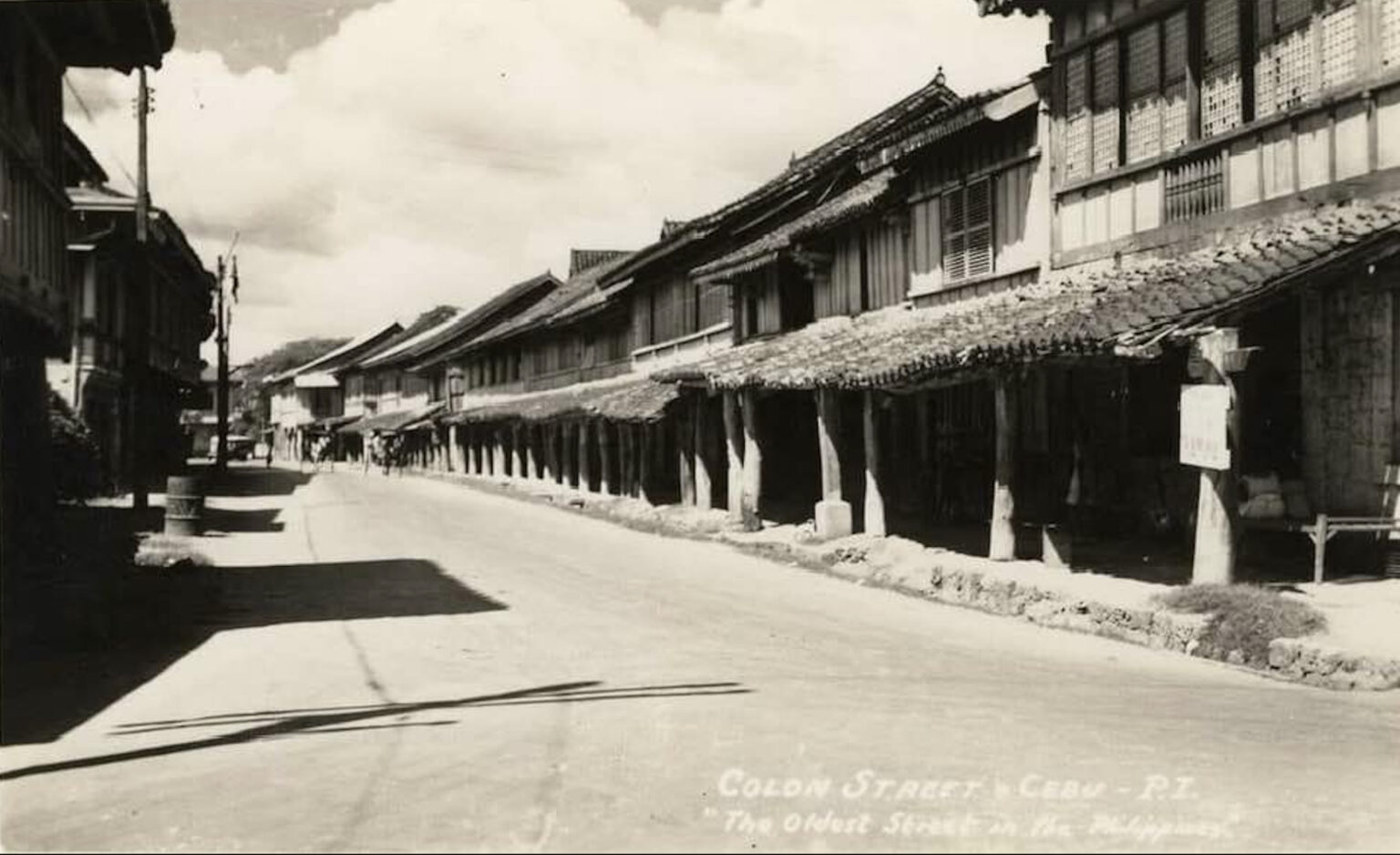

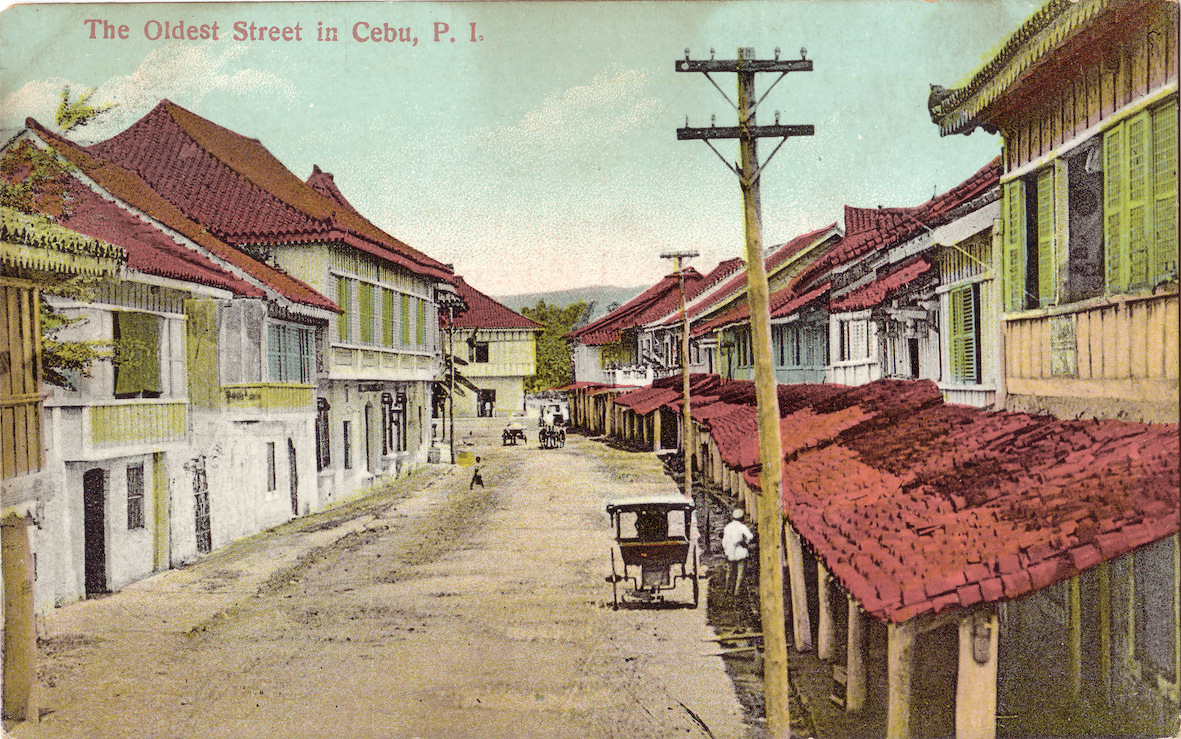

What is known is that sometime in 1910, a shop called American Bazar started peddling what may be considered the first postcard printed in Cebu (Mojares, n.d.). It featured the Parian section of Calle Colon as it looked on its northwestern tail-end with the label “Oldest Street in Cebu.” This was of an image shot by Dean Curran Tatom, an American soldier who had returned to Cebu that same year to revive a photo studio he established in 1901 which he folded some years later when he moved to Iloilo as the official photographer of the Philippine Railway Company (The Cebu Chronicle, 1910).

With so many US soldiers camped at Warwick Barracks eager to send an image of Cebu back home, sales of this postcard soon increased. And the myth began to take hold.

By around 1913-17, L.G. Joseph, another Cebu-based photo studio, also printed its own postcards of the same street, labeling it this time with the bold claim: “Oldest Street in the Philippines.” Some 15 years later, the international travel agency, American Express Company, further “institutionalized” this claim with its first-ever guidebook of the Philippines in 1933 (American Express Company).

Why Colon?

When the American flag was first raised in Cebu that fateful day of February 22, 1899, this short section of the long street named after Christopher Columbus happened to host the only remaining part of the city that was still thoroughly lined on both sides with old tile-roofed stone houses, locally called balay nga tisa, with their tell-tale ground floor tile-roofed arcades or canopies (called tiamtam in Chinese and tapangko in Cebuano) that stretched four meters over the sidewalk.

There used to be a lot of these two-story trading houses on other streets of the city, especially those near the waterfront. But in the aftermath of the 1898 Tres de Abril revolt, the Spanish gunboats, Maria Cristina and Paragua, pounded the waterfront and the city’s commercial district, erasing nearly a century of progress.

During the first decade of the 20th century therefore, much of the city was rebuilding, literally, with its commercial district, centered on Magallanes Street and its intersections, beginning to take on the trappings of American commercial architecture of the period, two-story buildings generally made of painted and highly embellished wood frames topped with galvanized iron roofing, so uncharacteristic of an ancient city and therefore not worth putting on postcards depicting old Cebu. Calle Colon, or at least that section in the Parian district, was thus the one and only likely candidate.

Where is the Oldest Street?

It is a wonder why even historians of the recent past never questioned how the oldest street in the Philippines can possibly be located about a kilometer inland in a city so famed in Rajah Humabon’s time for its vibrant trading port.

Did not the conqueror Miguel Lopez de Legazpi establish in 1565 a fort abutting that same waterfront and from there a villa, the beginnings of a Spanish ciudad? The earliest known map of Cebu City, dated to 1699, for example, shows the “ciudad” bordered on the west by the Estero de Parian, which is located between present-day Colon and Manalili streets. Colon, thus, was clearly outside of the ciudad and its streets.

Following the Laws of the Indies, Legazpi and his successors were duty-bound to build streets in grid-like pattern surrounding a public square or plaza (which one does not find in Colon). On one side of this square would be a church and across it the Cabildo or Casa Tribunal, seat of civilian authority. Perhaps a market would be on another side and, across this the houses of Spanish residents.

That plaza is none other than Plaza Sugbu today, the same public square that Humabon had offered to Magellan when the latter asked where the historic first baptism (on April 14, 1521) would be held, the same spot marked today by the Magellan’s Kiosk, which was once traversed by Calle Magallanes.

If there is a veritable candidate as the oldest street in the Philippines, therefore, it is without doubt Calle Magallanes, so aptly named by the Spaniards for their fallen explorer, and not one named after another who never even set foot in the Philippines.

Alarm bells should have rung in people’s minds when the claim to fame for Colon was first foisted. Commonsense logic would have dictated otherwise.